The History of Old City Hall

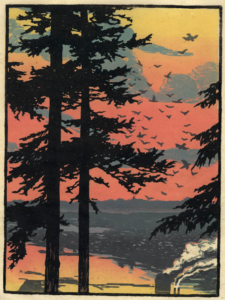

Reaching into the sky with its four spires and clock tower, Old City Hall is one of Bellingham’s most iconic landmarks. Most have seen the building and many have been inside during a visit to the Whatcom Museum. But fewer people know the history behind it — and the many secrets it holds.

History of Old City Hall

The story of Old City Hall starts more than 100 years ago. Prior to 1891, the New Whatcom City Council had been housed in the Oakland Block at the corner of Champion and Holly streets. The City Council shared space with a clothing store, a music dealer and a hotel.

However, as the government grew, it became evident that the City Council needed something bigger. They asked local architects to submit plans for a new city hall. In November, the council accepted a design from local architect Alfred Lee.

Lee, a self-taught architect, pulled the designs for the late-Victorian building from various catalogues and combined different plans together.

The beginning

The council purchased a plot of land on a bluff overlooking Bellingham Bluff for $5,000. Construction started in February 1892. Construction wrapped up quickly when an economic depression in 1893 caused funds for the project to disappear, leaving the second and third floor interiors unfinished.

One side effect caused by this abrupt stop was that the clock faces that had been installed didn’t actually work. Instead, the city moved the hands on the clock to permanently read seven o’clock. These didn’t last long, however, as strong winds eventually knocked out the clock faces. The city, not having the funds to replace them, simply left them as gaping holes.

The city did install a large, three-feet-in-diameter bell in the tower, which was rung to alert the volunteer fire department whenever there was a fire in the city. The height of the building made it easy to see any fires in the area.

City Hall is finished

As money slowly trickled in, construction continued on the building. The second and third floors’ interiors were finished in 1910. In total, the entire project costed $50,000 (about 1.3 million dollars today). City Council and other city employees slowly began to occupy the various rooms in the building. Today, visitors to Old City Hall can see where these officials worked by looking at the small black text panels that are next to select doors.

When New Whatcom and Fairhaven combined to form one town on Bellingham Bay in 1904, the New Whatcom City Hall on Prospect Street became the city hall for Bellingham. It continued to serve as city hall until the local departments physically outgrew the space. A newer, larger, and more modern city hall was built on Lottie Street in 1939, which still serves as Bellingham’s city hall.

Old City Hall sat empty for most of the 1939. There were calls from city councilmen to demolish the building. But the building was saved in November of that year when a group of volunteers led by John M. Edson established the Bellingham Public Museum Society and committed to occupy the building under a five-year lease. The museum officially opened on January 23, 1941.

The Museum

In 1962 a fire caused by faulty wiring ran through the top section of the building and left the main tower and much of the roof a charred frame of what it once was. Many thought that the building would be closed for good as it was no longer suitable for exhibition. A 12-year fundraising drive commenced.

Blueprints for the clock tower portion of the building no longer existed, so builders had to use photographs and sketches to recreate that section of the building. In 1974 the museum was finally reopened to the public. A bedsheet with the words “We Did It” was raised on the flag pole at the top of the tower.

Remnants of the history of Old City Hall can still be seen today. In the basement of the building, which used to serve as the city’s police station, the remains of jail bars over some doors and a padded jail cell can still be seen.

In the first floor photo gallery that is directly in front of the stairs, which used to be the city’s comptroller’s office, the outlines of what was once the comptroller’s vault can be faintly seen in the wall, covered by paint and a photograph. Behind the attendant’s desk, the remnants of the treasurer’s vault can be seen.

If you look up at the clock tower, there is a chance that the hands still read seven o’clock. The clock mechanism was never installed, so occasionally museum staff will climb up to the clock tower and move the hands.

Come discover the history of Old City Hall for yourself! Take a docent-led tour on Sunday afternoons at 12:30pm for more tales from the past.

–Written by Colton Redtfeldt, Marketing Assistant