Collaborative Effort: The Making of El Zodíaco Familiar

/0 Comments/in Uncategorized /by Christina Claassen

In El Zodíaco Familiar, those born in 1984 were not born in the year of the rat. Instead, they were born in the year of the chapulín, or grasshopper.

This exhibition is the fifth iteration of sculptor and ceramic artist George Rodriguez’s playful and personalized reinterpretation of the Chinese zodiac. In the series, Rodriguez reimagines the classic zodiac animals as analogous creatures of Mexican origin, bridging cultures and creating new narratives.

The sculptures on view are a collaborative effort between Rodriguez and 13 Mexican and ChicanX/Chicane artists of various artistic disciplines.

“The goal of this project and collaboration is to showcase the breath of artistic expressions within the Mexican and ChicanX community, to give these artists a platform to express their voice and vision, and to use a familiar tale to comment on the need for human connection and community,” Rodriguez writes.

El Zodíaco Familiar

When reimaging the zodiac signs, Rodriguez says he considers the characteristics of the traditional animals. That’s how he chose the grasshopper to represent the rat.

“The rat is sneaky and stealthy, and for me the grasshopper is very similar,” he explains. “You can hear them, and you know that they’re around, but you can’t see them. It’s the correlation of resiliency and stealthiness.”

The grasshopper is also more connected to Mexico than the rat.

“Rats are everywhere, but they aren’t a cultural icon of Mexico,” he says.

One requirement for the series is that artists work on the zodiac animal that corresponds with their birth year.

“The history of the zodiac is directly connected to people,” Rodriguez says. “I don’t get to choose the animal that I’m born into, but I can choose which characteristics I decide to take on.”

Rodriguez also wanted to feature a diverse range of techniques and forms, from fiber arts to photography to poetry.

“I know the clay part, but I wanted to know their art forms and how to incorporate that into a new piece,” he says.

All the sculptures use Rodriguez’s ceramic base forms for continuity. But that’s where the similarities end. Each sculpture incorporates different materials and perspectives.

Guerrero (Quetzalcoatl) by Rodriguez and Yosimar Reyes includes an audio component. Visitors can listen to the words of Reyes’ 86-year-old grandmother.

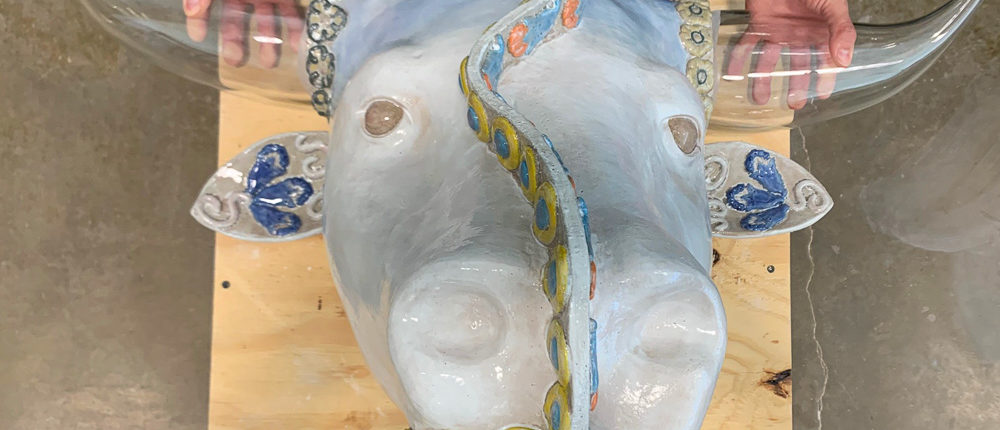

For Recollections—Atravesando con el Toro, Rodriguez’s collaboration with photographer and educator Marilyn Montúfar, their family histories in the United States and Mexico are seen in photographs transferred onto the bull’s face. Some are archive photos of parents and grandparents, while others were taken by Montúfar.

And in La Peyotera (Mono), Rodriguez’s collaboration with Gabriela Ramírez Michel, the sculpture’s face is brought to life by colorful yarn.

A Collaborative Process

Each collaboration is different, but Rodriguez says most start by brainstorming ideas. Some of the artists were able to visit his studio in Seattle. In other cases, Rodriguez would begin the sculpture and then ship it to the artist.

Over the last year, Rodriguez sent his ceramic base forms to artists in California, Illinois, Minnesota, New York, Texas, Washington, and Jalisco, Mexico.

With 1977 (Iguana), Rodriguez cut the dewlap – the skin under the iguana’s chin – into the shape of the U.S./Mexico border. Artist Eric J. Garcia then completed the illustration work in Minneapolis.

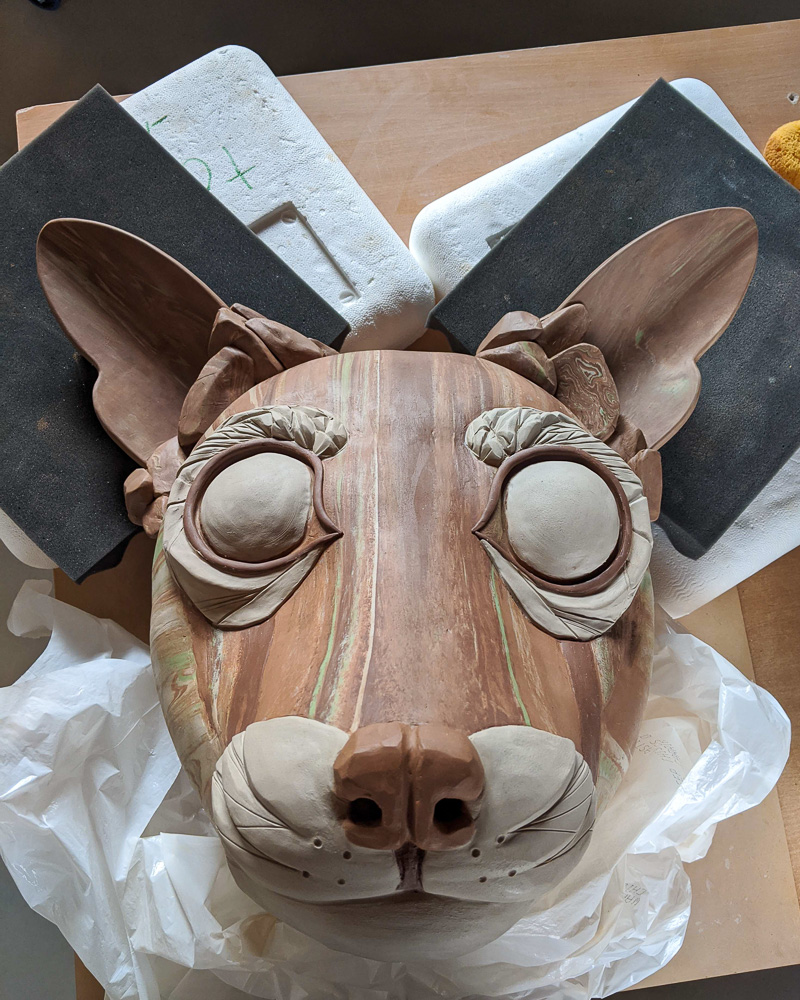

For Rodriguez’s collaboration with Samirah Steinmeyer on Cacomixtle del Desierto Sonorense, they had to get creative.

Since Steinmeyer, who is based in Arizona, was going to be using marbled clay throughout the piece, she had to construct the base herself. Rather than ship a pre-made base, Rodriguez sent her a four-part plaster mold and detailed instructions about how to use it.

“It was kind of intimidating,” Steinmeyer recalls. “I was unfamiliar with certain parts of the process, but I was up for the challenge.”

For her sculpture, Steinmeyer incorporated material from the nearby Sonoran Desert canyons.

“I took a hammer and crushed the rocks, experimenting with the grain size and how it would respond to firing in porcelain,” she explains.

She added those minerals to clay, marbling it in with other clay layers to form a patterned base.

Rodriguez says he was always excited to see how the sculptures turned out.

“I had some expectations of what the pieces would look like because I know the artists, but the sculptures always looked way different and way better than I could have imagined,” he says.

Sharing Experiences

Through text panels in English and Spanish, the exhibition allows the artists to share their process and stories.

In Recollections—Atravesando con el Toro by Rodriguez and Montúfar, a reference to the wall dividing the U.S./Mexico border runs down the bull’s face. Pink crosses labeled Ni Una Más (not one more woman missing) reference the missing women and ongoing femicide in Juárez.

“Painter Vincent Valdez has been creating artwork that touches upon resisting collective amnesia within the United States, meaning sometimes history is forgotten,” Montúfar says. “Parts of Texas and California were once Mexico, and I would like for people to continue talking about the history of these locations.”

Montúfar says her intention through the collaboration is to share experiences, stories, and histories.

That theme is reflected throughout the exhibition.

Ramírez Michel writes that La Peyotera is a celebration of life and a tribute to the Wixarika (Huichol) people.

“It is pure joy, hope, and above all a declaration of love to my country, Mexico,” her gallery label reads.

As for Rodriguez, he hopes the exhibition helps visitors discover new artists and their works.

“There’s storytelling in each animal, and I really hope that people will seek out the artists they like,” he says.

See El Zodíaco Familiar

El Zodíaco Familiar is on view in the Lightcatcher building through Oct. 24, 2021. The gallery labels and texts are in both English and Spanish.

Want to take a deeper dive into the exhibition? We’re offering guided docent tours in English and Spanish as well. You can learn more about the tours here.

For a list of participating artists and their zodiacs, as well as links to see more of their work, check out the exhibition web page.