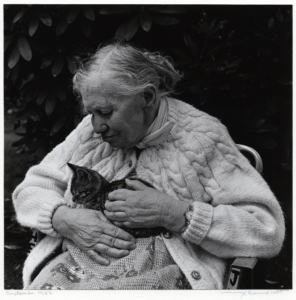

Five Women Artists in the Collection: Helen A. Loggie

The Whatcom Museum is featuring five women artists from its collection throughout the month of March—Women’s History Month—in conjunction with the #5WomenArtists campaign. The campaign is organized by the National Museum of Women in the Arts. This week we’re highlighting Helen A Loggie, whose work was last exhibited in the Whatcom Museum’s 2016 show, Just Women, as well as in the 2010 exhibition Show of Hands: Northwest Women Artists, 1880-2010.

Helen A Loggie early years

Helen A Loggie (1895–1976) was best known for her etchings depicting the Pacific Northwest landscape of the early- to mid-twentieth century, and particularly the trees that occupied her surroundings.

Loggie’s family settled in Bellingham the year she was born to operate a lumber mill at the mouth of Whatcom Creek. Surrounded by the lumber industry and forests, trees became central to Loggie in her later work. But her initial interests in art centered on portraiture.

In 1916 she moved to New York City to study at the Art Students League where she took her first formal courses in drawing and painting. It was there she learned the etching process that would later become the basis of her life’s work.

Travels and interest in Renaissance art took her to Europe numerous times during the 1920s where she sketched bustling city scenes. But the Pacific Northwest called her home. She settled in Bellingham in 1927 and found “a clarity of vision” within the landscape and culture of her childhood.

Life in Bellingham

Her practice was to draw outdoors during the spring and summer on Orcas Island or in the mountains. Using her drawings as her source imagery, she worked on her etchings during the fall and winter in her studio in Bellingham, though it was not uncommon for her to draw in nature even in the coldest months.

Many of her images are of specific places and even specific trees, which she infused with anthropomorphic qualities. For instance, a gnarled and twisted juniper tree she often depicted, which was located on a small island off the coast of her Orcas Island home, was called King Goblin. A version of Goblin resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hemlock Forest was one of the last etchings that Loggie completed before her death. It took her three to five years to complete. The dense, overall composition and areas of scribbled, calligraphic marks and vertical texture make it one of the more abstract works and conveys a certain spiritual quality. As in this and many other works, Loggie’s trees are both intimate portraits and elaborate cathedrals of the natural world.

-Compiled and written by Amy Chaloupka, Curator of Art